Published by Vilette Veil • 22 June 2025

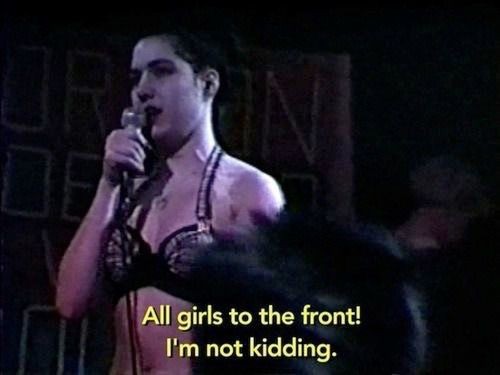

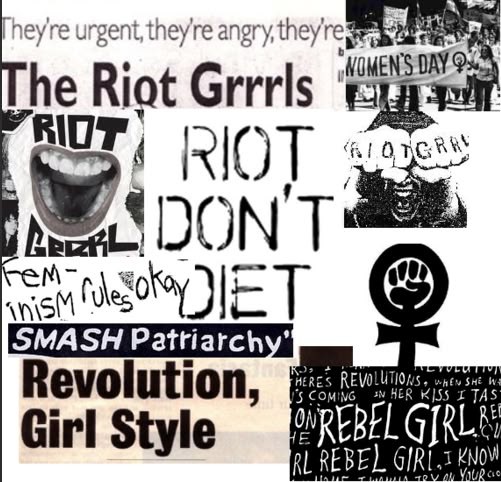

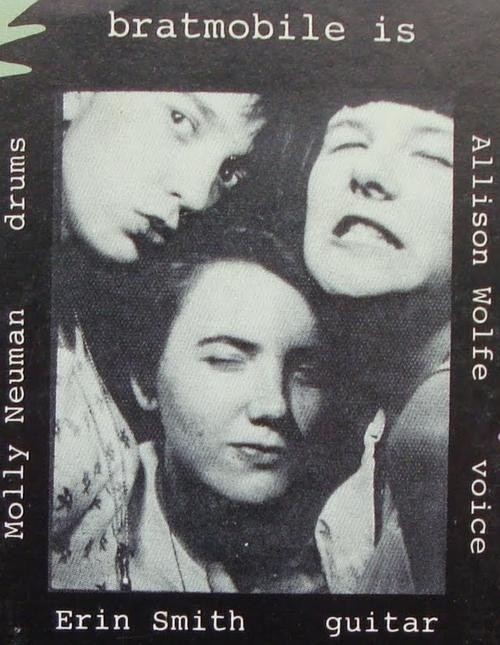

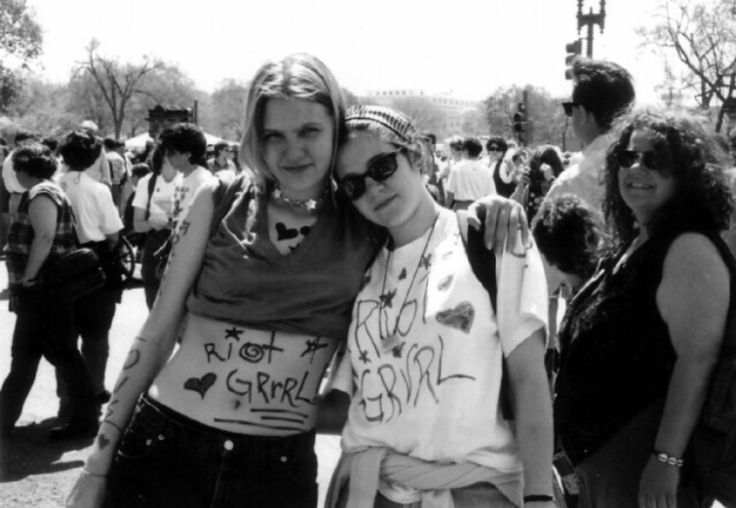

It wasn’t just punk. Riot Grrrl was a battle cry. A political movement in a mini skirt, screaming through cassette static and zine pages. It was 1990s Olympia and D.C. basements, where girls learned to plug in amps, play three chords, and burn the world down with them. Bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy weren’t just making noise; they were making space — for anger, softness, queerness, girlhood, survival.

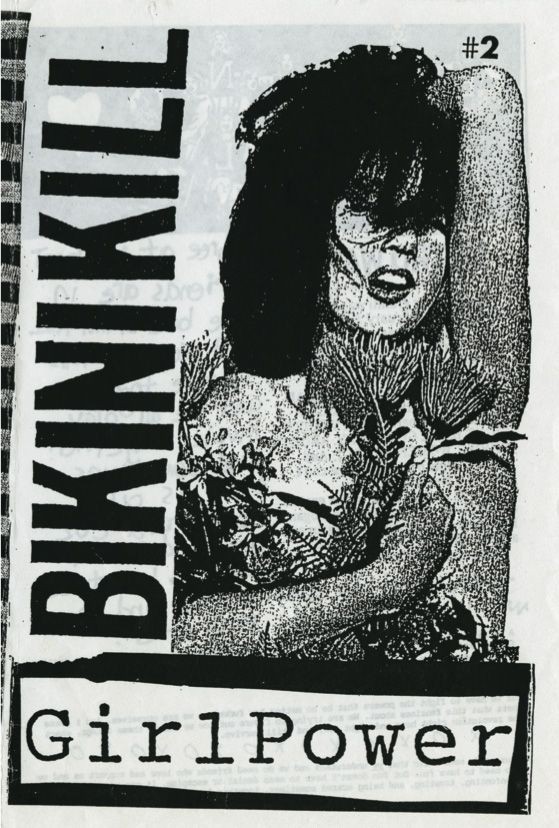

This was a time before social media could hold your trauma in a thread. Riot Grrrls made Xeroxed manifestos. They passed notes in the form of zines: hand-scrawled, gut-spilled, never proofread. They were talking about things most people still whisper about: rape, incest, body image, gender dysphoria, eating disorders. They put glitter on the scars and said: we’re still here.

Bands didn’t ask for permission. Riot Grrrl was DIY or die — every guitar riff snarled with defiance. Bikini Kill shouted with bloody-knuckle honesty while Bratmobile laughed at the absurdity of being a girl in a world built for boys.

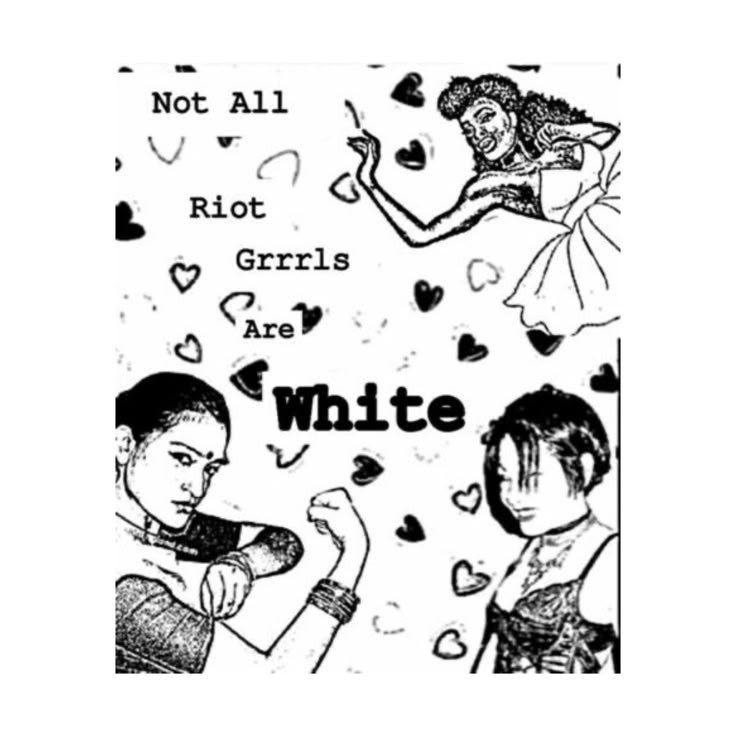

But let’s be real — Riot Grrrl wasn’t perfect. It had a whiteness problem. The spaces created often felt exclusive to white punk girls, and the movement’s language didn’t always leave room for Black, brown, or trans grrrls. It’s something the modern scene is still trying to heal and reckon with. Today’s Riot kids are building something more intersectional — and way more real.

You hear it in today’s bedroom punk producers and zine-makers on TikTok. You see it in queer punk nights and trans-fronted screamo bands. The underground still breathes — and it's screaming louder than ever.

What Riot Grrrl gave us wasn’t a polished legacy. It gave us permission. You don’t need to be good. You don’t need to be nice. You don’t need permission to make art, to be loud, to take up space, or to bleed onto a page and call it your power. Riot Grrrl is dead. Long live Riot Grrrl.